The Wing Chun wooden dummy, or Mook Yan Jong, is an iconic symbol of the art.

A silent training partner that has been instrumental in developing the skills of countless practitioners.

But how much do we really know about its history?

And how accurately do modern replicas reflect the training tools of the past?

This post delves into the fascinating history of the Wing Chun dummy, exploring its evolution and the quest for historical accuracy in its replication.

From Ancient Origins to a Martial Arts Icon

The concept of a wooden training partner is not unique to Wing Chun.

Historical records suggest that similar devices have been used in Chinese martial arts for centuries.

The earliest known reference comes from Sima Qian, a historian from the 2nd and 1st centuries BCE,

who wrote about Emperor Wu Yi of the Shang dynasty (circa 1200 BCE) using a wooden figure for combat practice.

Over time, these training tools became more sophisticated.

By the time Wing Chun began to flourish, the wooden dummy was a common sight in southern China.

It was particularly popular among Cantonese Opera performers,

who used it to hone their martial skills for their physically demanding roles.

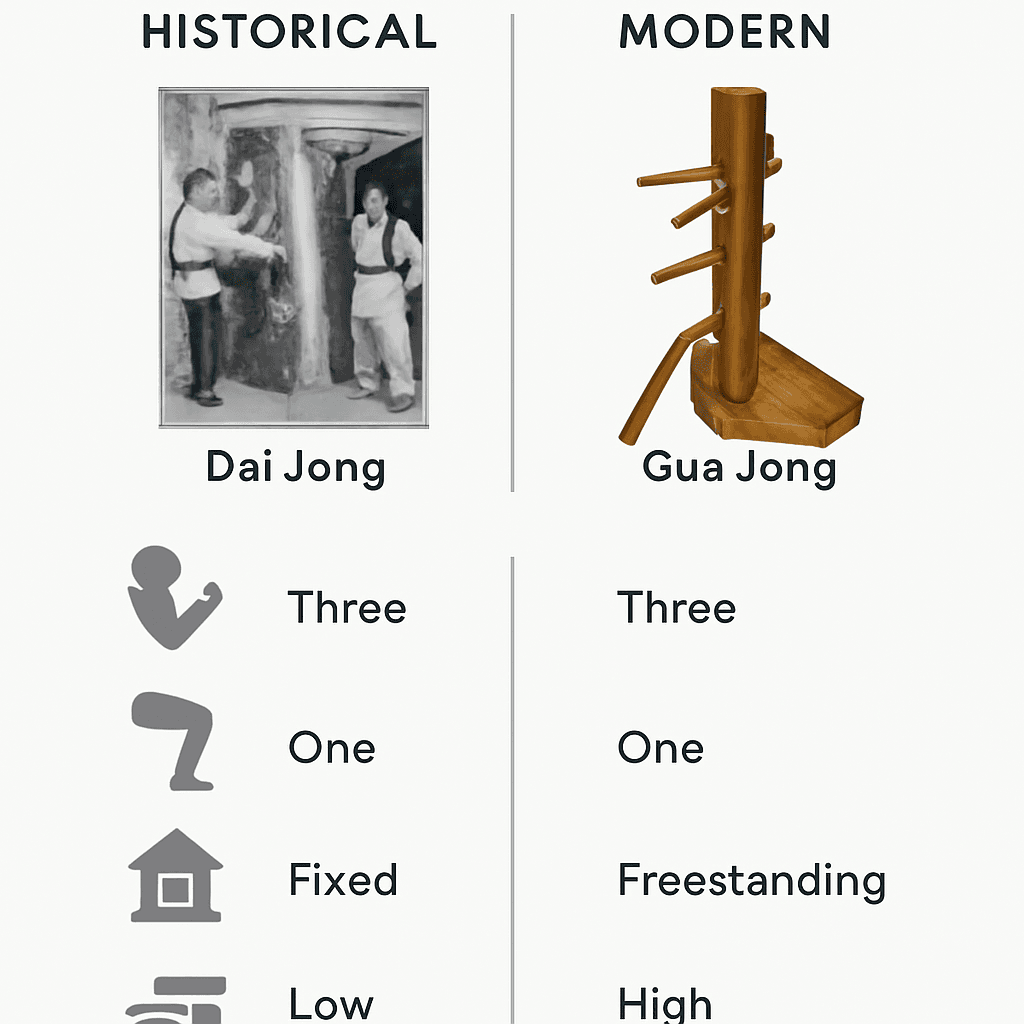

Many of these early dummies, known as Dai Jong or “ground dummies,” were large, heavy posts buried in the ground.

This design provided a stable and unyielding opponent, perfect for developing power and structure.

These early dummies were typically made from a single log, with the lower portion squared off and buried in a pit.

The pit was often filled with materials like shredded rattan to provide a degree of “springiness,”

allowing the dummy to absorb and react to strikes.

While the basic design of three arms and one leg was present, the dimensions and arm configuration could vary.

Many historical examples feature thick, offset arms, differing from the parallel arms common in many modern lineages.

Ip Man and the Modern Wing Chun Dummy

The 20th century brought significant changes to the world of martial arts, and the Wing Chun dummy was no exception.

The most pivotal figure in the modernization of the dummy is undoubtedly Grandmaster Ip Man.

When Ip Man moved from Foshan to Hong Kong, he faced a new set of challenges.

The dense urban environment of Hong Kong made the traditional Dai Jong impractical.

There was simply no space to bury a large wooden post in the ground.

This necessity led to innovation. Ip Man is credited with developing the “Gua Jong,” or hanging dummy.

This new design mounted the dummy on a frame, allowing it to be used in smaller spaces.

This adaptation not only made the dummy more accessible to urban dwellers but also introduced a new dynamic to the training.

The hanging dummy, with its ability to move and recoil, more closely mimics the reactions of a live opponent, fostering the development of sensitivity and adaptability.

Ip Man’s design, with its three arms and one leg, has become the standard for modern Wing Chun dummies.

However, it’s important to remember that this is just one branch of the dummy’s evolutionary tree.

Other lineages and styles of Wing Chun have their own variations, each with its own unique history and training methodology.

The Quest for Historical Accuracy in Replication

Given the rich history and evolution of the Wing Chun dummy, the question of historical accuracy in modern replicas becomes pertinent.

Is it important for a modern dummy to precisely replicate an ancient one? The answer depends on the practitioner’s goals.

For those interested in preserving the historical integrity of Wing Chun as it was practiced in specific eras, replicating older dummy designs can be invaluable.

Training on a Dai Jong, for instance, would provide a different tactile experience and emphasize different aspects of force generation and body mechanics compared to a modern Gua Jong.

This kind of replication allows for a deeper understanding of the art’s historical context and the training methods that shaped its development.

However, for the majority of practitioners, the focus is on effective training for self-defense and skill development in the present day.

In this context, the functionality of the dummy often takes precedence over strict historical adherence.

Modern dummies, while rooted in traditional designs, have been refined to suit contemporary training environments and pedagogical approaches.

The key is that the dummy, regardless of its specific design, serves its purpose as a tool to develop proper structure, angles, footwork, and sensitivity.

Ultimately, the historical accuracy of a Wing Chun dummy replication lies not just in its physical form,

but in its ability to facilitate the core principles and techniques of Wing Chun.

Whether you train on a replica of an ancient Dai Jong or a modern Gua Jong, the true value lies in the dedication and understanding you bring to your practice.

What are your thoughts on the evolution of the Wing Chun dummy?

Share your experiences and insights in the comments below!