Wing Chun is a traditional Chinese martial art that has gained worldwide recognition for its efficiency, directness, and practicality. 6 Gates in Wing Chun.

Originating from Southern China.

this system of self-defense emphasizes close-range combat and rapid, precise movements.

The effectiveness of Wing Chun lies in its core principles, which form the bedrock of its techniques and strategies.

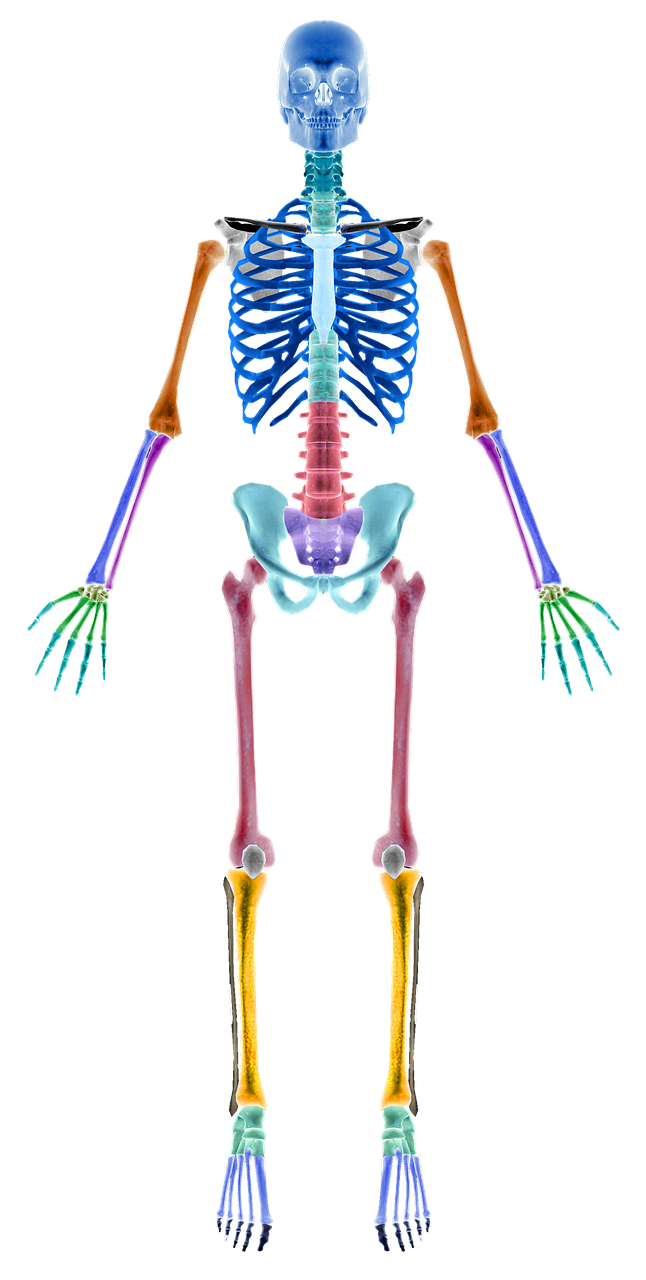

One of the fundamental principles of Wing Chun is the centerline theory.

This concept revolves around the idea that the centerline, an imaginary vertical line running down the middle of the body, is the most vulnerable and vital area in combat.

By controlling the centerline, a practitioner can effectively dominate the opponent’s movements and protect their own vital areas.

Strikes and defenses are designed to either attack the opponent’s centerline or defend one’s own, making the centerline theory a pivotal aspect of Wing Chun.

Another essential principle is the economy of motion.

Wing Chun techniques are characterized by their simplicity and directness, ensuring that no unnecessary movements are made.

This principle allows practitioners to conserve energy and maintain a high level of efficiency during combat.

By minimizing extraneous actions, Wing Chun enables quick, powerful responses that are both effective and energy-efficient.

Simultaneous attack and defense is another key element of Wing Chun.

Unlike many martial arts that separate offensive and defensive actions, Wing Chun integrates them into a single, fluid motion.

This approach not only increases the speed of response but also maximizes the effectiveness of each movement.

By combining attack and defense, practitioners can create opportunities to strike while neutralizing incoming threats.

These

- principles —

- centerline theory,

- economy of motion,

- and simultaneous attack and defens —

provide a robust framework for understanding and applying Wing Chun techniques.

With this foundational knowledge, one can better appreciate the concept of the 6 gates, which are integral to the practice and application of Wing Chun in real-world scenarios.

What Are the 6 Gates in Wing Chun?

In Wing Chun, the concept of the 6 gates is fundamental to both defense and offense.

These gates are imaginary lines that divide the body into distinct zones, helping practitioners to strategically manage attacks and counters.

Essentially, the 6 gates are divided into upper, middle, and lower sections, each of which is further split between the left and right sides of the body.

The upper gates cover the area from the top of the head to the shoulders.

These zones are crucial for defending against high-line attacks, such as punches or strikes aimed at the head and neck.

The middle gates span from the shoulders to the waist, protecting the torso and vital organs.

This is often the focal point in many encounters, as attacks to the middle gate can be particularly debilitating.

The lower gates extend from the waist down to the legs, guarding against low-line attacks like kicks or sweeps.

By dividing the body into these six distinct gates, Wing Chun practitioners can efficiently allocate their defensive and offensive efforts.

For example, when an attack is directed at the left upper gate, the practitioner can quickly respond with a block or counter from that specific zone.

This structured approach not only simplifies the decision-making process during a confrontation but also maximizes the effectiveness of movements and techniques.

Visualizing the 6 gates can significantly enhance one’s understanding and application of Wing Chun.

Diagrams or visual aids are often used to illustrate these zones, providing a clearer picture of how they align with the body’s natural lines of defense and attack.

By mastering the concept of the 6 gates, practitioners can develop a more nuanced and effective approach to both offense and defense in Wing Chun.

The Upper Gates: Zones of Defense and Attack

The upper gates in Wing Chun, which encompass the head and shoulders area, are crucial for both defense and offense.

Mastering the techniques associated with these gates can provide a significant advantage in any confrontation.

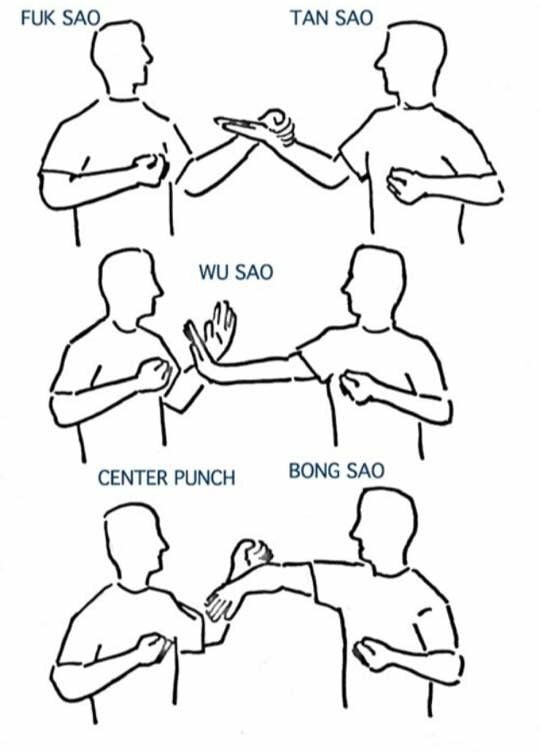

Among the primary defensive techniques used to protect the upper gates are Tan Sau, Bong Sau, and Pak Sau.

Each of these techniques offers unique benefits and applications in real-world scenarios.

Tan Sau, or the “palm-up hand,” is pivotal for intercepting and deflecting incoming strikes aimed at the head and shoulders.

This technique not only provides a shield for the upper gates but also positions the practitioner for immediate counterattacks.

The Bong Sau, or “wing arm,” is another essential upper gate defensive maneuver.

It involves raising the arm to create a barrier that deflects attacks away from the centerline.

This technique is particularly effective against high punches and hooks, as it redirects the opponent’s energy and opens them up for counterstrikes.

Pak Sau, or the “slapping hand,” is used to parry and control the opponent’s limbs, preventing them from launching effective attacks while simultaneously setting up opportunities for retaliation.

On the offensive front, the upper gates offer a range of striking options.

High punches, such as the straight punch or the chain punch, can be delivered with speed and precision from this zone.

These strikes aim to overwhelm the opponent’s defenses and target vulnerable areas like the face and throat.

Additionally, elbow strikes can be executed from the upper gates, providing powerful and close-range offensive tools.

These strikes are particularly effective in trapping and grappling situations, where the distance between opponents is minimized.

In summary, understanding and effectively utilizing the upper gates in Wing Chun can significantly enhance a practitioner’s defensive and offensive capabilities.

By mastering techniques like Tan Sau, Bong Sau, and Pak Sau, and incorporating high punches and elbow strikes, one can develop a comprehensive approach to managing the head and shoulders area in combat.

The Middle Gates: Core Protection and Offense

The middle gates in Wing Chun serve as a critical area for both defense and offense, focusing on the protection of the torso and chest.

Mastering this region is essential for any practitioner.

As it involves a range of techniques that allow for fluid transitions between defensive and offensive maneuvers.

The middle gates are the battleground where techniques like Fook Sau, Lap Sau, and the Wing Chun punch come into play, each offering unique advantages and applications.

Fook Sau, or “Controlling Hand,” is a fundamental technique utilized to manage an opponent’s arm.

providing both a defensive and offensive edge.

This technique helps maintain a tactile sensitivity to the opponent’s movements.

Allowing the practitioner to respond swiftly to any changes.

By applying Fook Sau, one can intercept incoming attacks while preparing to launch a counter-attack.

This dual functionality makes it a cornerstone of middle gate defense.

Lap Sau, known as “Grabbing Hand,” complements Fook Sau by facilitating a more aggressive approach.

This technique involves pulling or jerking the opponent’s arm to destabilize their balance, creating an opening for an immediate counter-attack.

Lap Sau is particularly effective when transitioning from a defensive posture to an offensive one.

Enabling the practitioner to seize control of the engagement and dictate the flow of combat.

The Wing Chun punch, or “Straight Punch,” is a direct and efficient striking technique designe to maximize power and speed.

Unlike traditional boxing punches that often rely on winding movements, the Wing Chun punch is delivered in a straight line, minimizing telegraphing and maximizing impact.

This technique is ideally suited for the middle gates, where quick, decisive strikes can capitalize on the openings created by Fook Sau and Lap Sau.

Seamless transition between defense and offense is vital in the middle gate area.

Practitioners must develop an intuitive understanding of when to switch from one to the other, maintaining fluidity in their movements.

This adaptability is achieve through consistent practice and a deep comprehension of the underlying principles of Wing Chun.

By mastering the middle gates, one can effectively protect the torso and chest while maintaining the capability to launch swift, powerful counter-attacks.

The Lower Gates: Defending and Attacking the Lower Body

In Wing Chun, the lower gates pertain to the legs and lower torso, critical areas in both defense and offense.

Understanding how to protect and attack these zones can significantly enhance a practitioner’s effectiveness in combat.

For defensive maneuvers, techniques such as the low Bong Sau and low Pak Sau are fundamental.

The low Bong Sau is a deflection move where the forearm is used to redirect an opponent’s low strike away from the body.

Allowing the practitioner to maintain balance and readiness for a counter-attack.

Similarly, the low Pak Sau involves using the palm to parry or slap away an incoming attack.

ensuring minimal disruption to one’s stance and offering the opportunity to respond swiftly.

On the offensive front, targeting an opponent’s lower gates can be highly effective.

Low kicks, which focus on the legs and knees, can disrupt an opponent’s balance and mobility.

Techniques such as the low front kick (Teep) and the low sidekick are designed to strike with precision and force, aiming to incapacitate the opponent’s ability to stand or move effectively.

Additionally, sweeps play a crucial role in Wing Chun’s offensive arsenal. By targeting an opponent’s ankles or lower legs, a well-executed sweep can bring the opponent to the ground, providing a strategic advantage.

Mastering the lower gates involves not only the physical execution of these techniques but also an understanding of timing and positioning.

Effective use of the lower gates requires the practitioner to be observant and responsive to an opponent’s movements, capitalizing on openings when they arise.

By integrating these defensive and offensive strategies, a Wing Chun practitioner can create a robust approach to managing combat scenarios.

ensuring comprehensive coverage of both upper and lower body defenses and attacks.

Combining the Gates: Fluidity and Transition

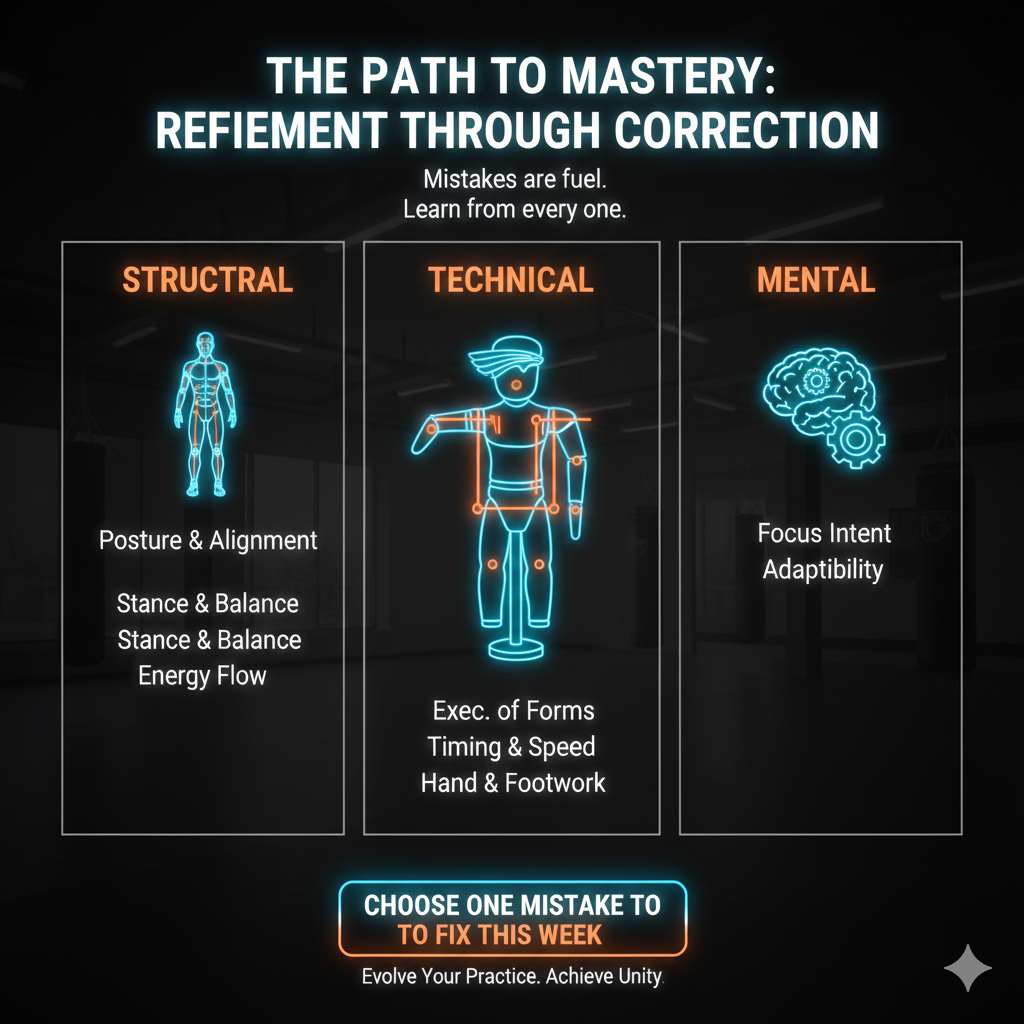

Effectively combining the six gates in Wing Chun requires not only an understanding of each gate individually.

but also the ability to transition smoothly between them during a confrontation.

Maintaining control of the centerline is paramount.

as it allows a practitioner to manage the opponent’s movements and keep the upper hand.

Fluidity in Wing Chun is achieve through continuous motion and adaptability.

Rather than thinking of the gates as static positions.

they should be view as dynamic points that can change rapidly in response to the opponent’s actions.

This adaptability ensures that no matter the angle or force of an attack, the practitioner can respond efficiently and effectively.

One crucial aspect of achieving fluidity is the concept of “sticky hands” or Chi Sau.

This training exercise emphasizes sensitivity and the ability to read an opponent’s intentions through touch.

Practitioners engage in a controll, continuous flow of movement.

focusing on maintaining contact and interpreting the opponent’s energy.

This drill helps in developing the reflexes necessary for smooth transitions between the gates.

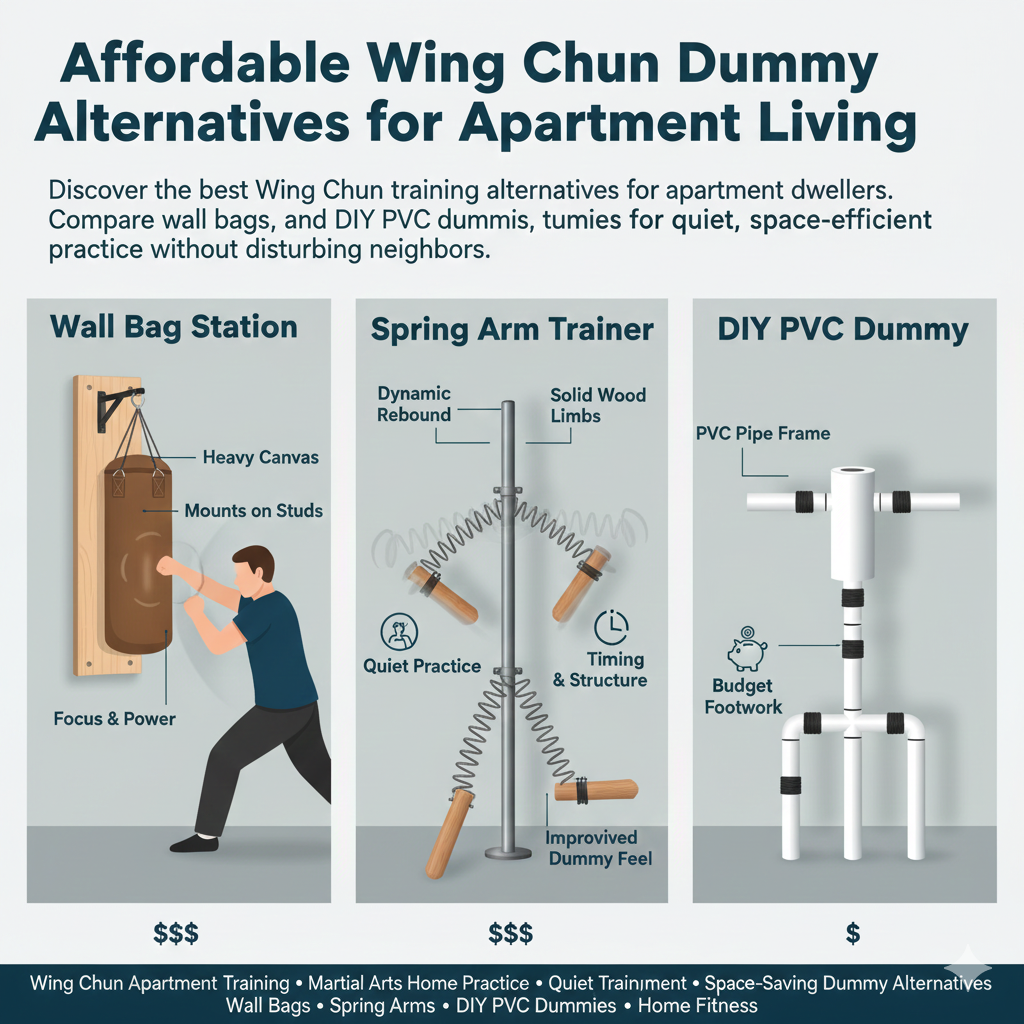

Another effective drill is the use of the Muk Yan Jong, or wooden dummy.

This traditional training tool allows practitioners to practice their techniques with precision.

Ensuring that each movement is executed correctly.

By incorporating the six gates into wooden dummy training.

practitioners can develop the muscle memory needed for fluid transitions in real combat scenarios.

Additionally, partner drills that simulate realistic attacks and defenses are essential.

These exercises should focus on maintaining control of the centerline while shifting seamlessly between the gates.

For instance, one partner can throw various punches and kicks.

while the other practices defending and countering by moving through the different gates.

Over time, these drills help to internalize the principles of fluidity and transition.

In essence, the key to mastering the six gates lies in understanding their interconnectedness and practicing the transitions diligently.

By focusing on fluidity and control of the centerline.

A Wing Chun practitioner can effectively neutralize an opponent’s attacks and maintain a dominant position throughout the confrontation.

Practical Applications: Scenarios and Techniques

In Wing Chun, the concept of the 6 gates is instrumental in managing both defense and offense.

These gates can be visualizes as zones around your body that need to be protect against strikes.

Understanding and applying these gates can significantly enhance your ability to defend against various types of attacks.

Let’s explore practical scenarios where the 6 gates come into play.

along with step-by-step techniques to effectively utilize them.

Defending Against a High Punch

When an opponent throws a high punch, such as a jab or a cross aimed at your head, the upper gates (high left and high right) become crucial.

To counter this, use the Tan Sao (palm-up hand) or Bong Sao (wing arm) techniques.

For instance, if a punch is direct at your right upper gate, execute a Bong Sao with your right arm to deflect the punch outward.

Simultaneously, step slightly to the side to avoid the direct line of attack.

Follow up with a counter-strike, such as a quick punch or palm strike to the opponent’s exposing area.

Defending Against a Mid-Level Strike

Mid-level strikes, such as hooks or body punches, target the mid-gates (middle left and middle right).

The Wu Sao (guarding hand) and Pak Sao (slapping hand) are effective techniques for these scenarios.

If an opponent throws a left hook towards your mid-gate, intercept it with a Pak Sao using your right hand.

pushing the punch away from your body.

Simultaneously, use your left Wu Sao to guard against a potential follow-up strike.

From this position, you can quickly counter with a punch to the opponent’s midsection or head.

Defending Against a Low Kick

Low kicks, targeting the lower gates (low left and low right), require a different approach.

The Gan Sao (low sweeping hand) and shifting techniques are essential here.

When facing a low kick aimed at your left leg, use your left Gan Sao to intercept and deflect the kick downward.

Concurrently, shift your weight onto the opposite leg to maintain balance and prepare for a counter-attack.

This could involve a quick step-in followed by a straight punch or a low kick to the opponent’s supporting leg.

By mastering these techniques and understanding the application of the 6 gates in Wing Chun.

Practitioners can effectively neutralize various attacks and gain a strategic advantage in real-world confrontations.

Each gate serves as a focal point for defense, allowing for seamless transitions between blocking and countering, thereby enhancing overall combat effectiveness.

Training Tips: Enhancing Your Skills with the 6 Gates

Mastering the 6 gates in Wing Chun requires dedication, consistent practice, and a strategic approach to training.

To enhance your skills effectively, consider incorporating partner drills, solo exercises.

and mindfulness techniques into your routine.

Each method serves a unique purpose in refining your understanding and application of the 6 gates.

Partner drills are essential for developing real-world application skills.

Practicing Chi Sau (sticking hands) with a partner allows you to experience live feedback and adjust your techniques accordingly.

Focus on maintaining proper structure and sensitivity to your partner’s movements.

This dynamic interaction will help you understand how to effectively use the gates against an opponent.

Regularly switch roles with your partner to gain a comprehensive understanding of both offensive and defensive techniques.

Solo exercises are equally important for building foundational skills.

Forms like Siu Nim Tao and Chum Kiu are critical in ingraining the principles of the 6 gates into your muscle memory.

Pay close attention to your stance, hand positions, and the flow of movements.

Shadowboxing can also be beneficial, as it allows you to visualize an opponent and practice transitions between the gates without external distractions.

Mindfulness and focus play a crucial role in Wing Chun training.

Being present and aware during practice sessions enhances your ability to react swiftly and accurately.

Techniques such as deep breathing and meditation can improve your mental clarity and concentration.

which are vital during both training and actual combat situations.

Aim to cultivate a calm and centered mind, enabling you to respond effectively under pressure.

For those looking to deepen their understanding, several resources can be invaluable.

Books like “Wing Chun Compendium” by Wayne Belonoha provide in-depth insights into the art.

Additionally, instructional videos and seminars by renowned Wing Chun masters offer practical demonstrations and advanced techniques.

Engaging with a community of practitioners, either online or in local schools, can also provide support and further learning opportunities.